BEST TECHNIQUES FOR INTRODUCING YOUR FICTIONAL WORLD

FASTEN YOUR SEAT BELT, DOROTHY, CAUSE KANSAS IS GOING BYE-BYE

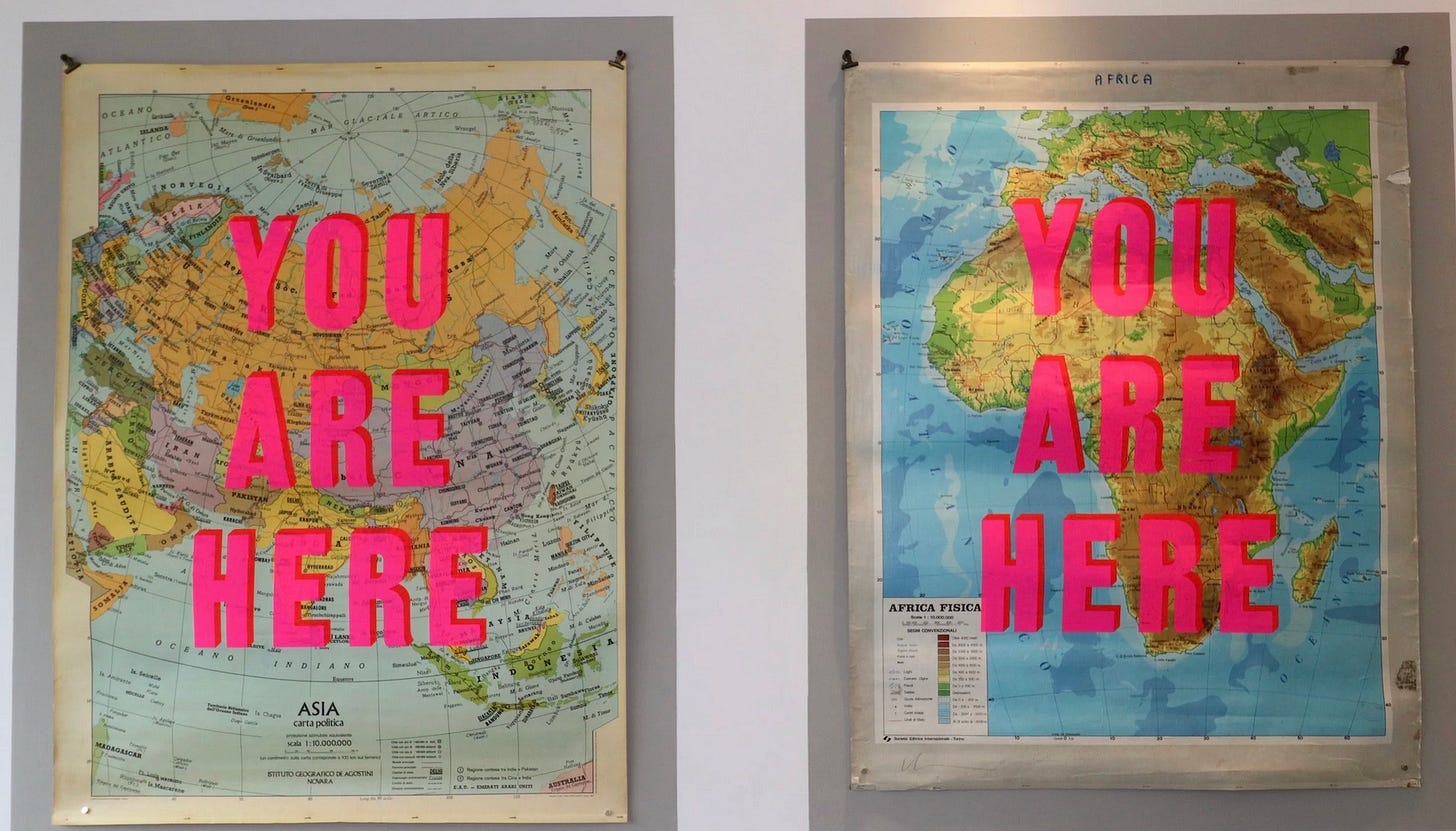

Nearly all fiction stories have settings, but most settings often don’t do much more than give the reader simple spatial coordinates, satisfy our environment-driven brains craving for a place — any place — to plant itself in. These types of settings are familiar in a banal literal sort of way. They are, for lack of a better term, commonplaces. Commonplaces are commonplaces because they are self-explanatory, are part of a common atlas. (Common to whom, you might rightly ask, but that’s a conversation for another time.) A writer, if they choose, can elaborate a commonplace, elevating it to something strange, to an uncommonplace — but they also can choose not to.

Commonplaces are settings that don’t require a lot of work from our readers.

Now don’t get it twisted: even the barest commonplace is an invaluable element of a story. Settings are essential in selling the reader that you, the writer, know how the world works and in satisfying a reader’s deep seated drive to place themselves, literally, in stories. Ultimately, stories without settings are rarely satisfactory stories. And yet for all their indispensability most settings don’t do much beyond placing us spatially and occasionally imparting some flavor, some character, some mood (though none of these are trivial to a well-told story, as I’ve discussed previously).

But there are stories, however, that require far more complex, demanding settings. Stories that make their settings an important character in the story.

Stories, in other words, that deploy worldbuilding to render their fictional worlds.

One might immediately assume I’m talking about obvious worldbuilding monuments like The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones and Dune and Dawn. Sure, but I’m also talking about E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Mantel’s Wolf Hall, Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, Francisco Goldman’s The Long Night of White Chickens, C. Pam Zhang’s How Much of These Hills Is Gold, John LeCarre’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, even my novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

Stories that are of this world, but whose narrative worlds are either outside of the common atlas (spatially / temporally) or are a marginalized part of the common atlas but have been rendered unrecognizable by hegemonic stereotypes and colonial distortions of a thousand kinds.

I’ve got some ideas about how one might bring our Worlds most fully and convincingly into our Stories — maybe too many ideas, as this Substack will soon (I hope) show — but for now I’m interested in how we writers introduce our Worlds in our Stories — what are the common strategies to signal to a reader that they are about to step through a wardrobe into Narnia, or as Cypher says in The Matrix: fasten your seat belt, Dorothy, ‘cause Kansas is going bye-bye.