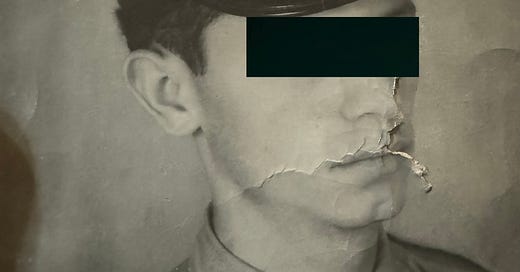

My father was a truly messed-up dude. He had gotten sideswiped by the 1965 Civil War — sideswiped completely. One moment at the top of the poor people pyramid, a military police officer with the crispest uniform since the invention of starch — and in the next he was on the run, everyone, it seemed, trying to murk his ass. My uncle, his younger brother, remembers that when the US invasion squashed the revolution and put the ex-Trujillastas back in power, my father returned home half-starved with a wild beard and a fist-sized blood blister on his shoulder from bracing his submachine gun.

I met him for the first time in New Jersey, nine years later. But you know how time is under the influence of trauma. To the world, my pops presented always as an affable dandy — and I mean it, too — homeboy might have been the best dressed Caribbean in a hundred mile radius (and if you knew the Cuban mampiolos from West New York you’d understand what an accomplishment that was) — but at home with us kids he acted like the war had never ended, like the revolutionaries were still shooting at him from every damn corner. Living with him was like living with a human version of the Emergency Broadcast Network.

Dude thought that everyone was coming for his neck. He had dozens of firearms in our little apartment, a white dude arsenal and enough ammunition to put down a local insurgency, and each weekend he took me and my brother to the Englishtown Rifle Range — and when he wasn’t chasing after his other women or beating the blood out of us for some random nonsense he put me and my brother through the ringer with his boxing bullshit. Whether because of him or because that was just our world I had at least one fight every quarter in school — not counting how often my brother and I went at it. One kid smashed my head so hard into a bathroom wall I threw up nonstop an entire afternoon and that was supposedly one of the few fights I won.

When I was nine my father started taking Taekwondo classes in Avenel, my first taste by displacement of Korean War trauma, and he brought all that shit home, as well. If then had been now, my old man would have been into jiu-jitsu hardcore, no doubt about it, maybe a survivalist (except he would have needed somewhere to hang his shirts). When we were bored my brother and I would handle my father’s firearms, and at night I tried to decide who I would shoot if I had to shoot someone.

Years later, I watched Red Dawn — this was after my father had skedaddled — and I realized that the Eckert Brothers were who he wanted us to be.

Did he really think we were going to be hunted by armed rebels or was he just being sadistic? Both, I’m sure. The first absolving — and obscuring — the second. Trust me. I remember right after he started Taekwondo he inaugurated our very own family fight club — just me and my brother in the basement with him as referee. He slapped — theatrically, mind you — a single dollar bill on the floor and whomever won the fight would claim that dollar.