I never had an easy time at my MFA. I’ve written a little about it before. Part of the problem was how far Ithaca was from anything I knew. Part of the problem was my own depressive states, especially during those long winters. But part of the problem was the whiteness of Ithaca in 1992. Might not have been as shocking if I’d done my undergraduate somewhere else, but I was a Rutgers kid. Rutgers might have had its drawbacks but lack of pigment wasn’t one of them. There were more Dominicans at Rutgers than there were students of color at Cornell — or at least, that’s how it seemed to me.

Still, I tried my best: at Ithaca and the MFA. I made friends, did my work, supported the program. Even had a little job arranging the catering for our MFA events (on top of the other job I had on campus). I definitely needed the money: those grad student stipends are only generous if you got loot coming in from elsewhere.

To keep a long story short: for all that troubled me about Cornell, I tried to make it work, tried to be part of the team, and I thought I did an OK job. My faculty advisor certainly seemed to like me. Had me over to their house plenty of times and we seemed to have a strong working relationship. They had me thinking about shaping my manuscript into a book, finding an agent, maybe even securing a Wallace Stegner Fellowship (a program they had strong connections at). Because of that faculty member’s attention, I started to feel like a favorite, not a status I was accustomed to at all.

That first year, at least.

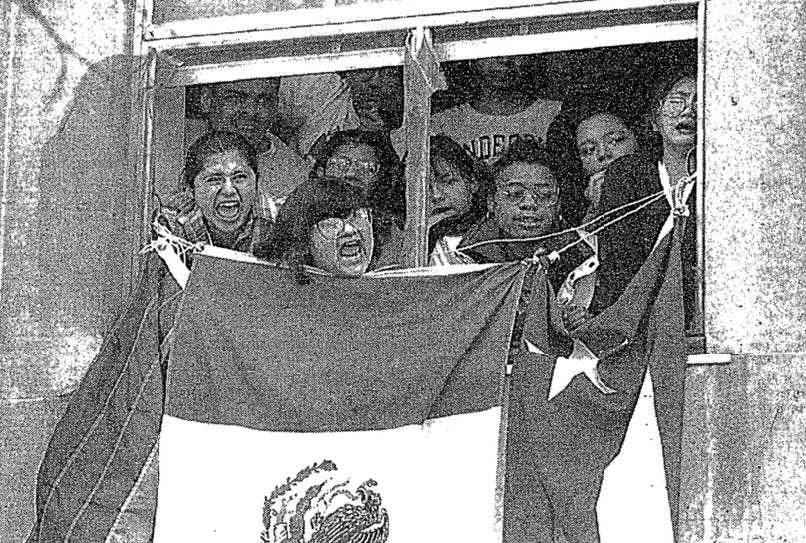

During the fall of my second year, a Latine student protest movement erupted, sparked by long simmering tension over Cornell’s lack of support for its Latine students, and by the racist graffiti that got scrawled over Daniel Joseph Martínez’s installation “The Castle is Burning”.

A group of Black and Latine students — mostly undergraduates — took over Day Hall and of course I got involved. But, like, really involved. One day I’ll have to write all about that whole wild experience because it turned out to be as prominent a part of my graduate life as even my writing. Turned out to be as prominent a part of my regular life, too.

There was a flight of us, Black, Latine, Asian-American, and even some white kids — one of whose last name was actually White. We were all super active for the next two years (and beyond). I was on the negotiation team with folks like Paula Moya, and despite all the resistance we faced from the administration, we students notched some solid victories. We secured six faculty lines in Latino Studies (as it was called at the time). In English / Creative Writing we were able to hire the magnificent Helena María Viramontes (how many students benefited from her mentorship and presence I cannot count). We got a student dorm called the Latino Living Center.

My last year at Cornell I was teaching on top of the other jobs, and I was writing and I was doing the activist work. As you might imagine something had to give, and what gave was the departmental piece. I had a choice between my very white department or a student of color movement, and I went with the color. I stopped participating in the MFA world as much, was no longer part of the team in the same way. Still went out with my departmental people for weekly drinks and dinner so it didn’t seem to be a huge problem.

Cue the sinister music.

That third year I decided to apply for a Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford. Movement or no movement, I needed a break from wintry Ithaca and felt like I had a chance; I had written two stories that read very strong (one of them would end up being published in Story, another in The New Yorker). Told my faculty people what I was doing. Told my advisor what I was doing. They said (and I quote): “Sounds great.” Started sharpening my portfolio, getting notes from my peers, and then a week before the deadline I had a meeting with my faculty advisor — to talk over my application, I figured.

I figured wrong.

My advisor didn’t wait for me to sit down before giving me a chilly smile. They then informed me, very nicely, that they would not write me a letter for the Stegner.

I was stunned. “Why?”

My advisor had an attendance book on their desk and turned it around to face me. Still smiling. “You missed out on a few workshops last semester, didn’t you?”

I looked at the attendance book and I looked at my advisor. And like that it all became clear: all of it. I might have been naïve but I wasn’t stupid.

What I realized was that my advisor had never said a word about my activism, had never so much as peeped when I joined the other graduate students in criticizing the English Department’s lack of diversity, when I rallied to bring Helena María Viramontes into the department.

Not one word for or against, but the entire time my advisor must have been steaming, seeing my actions as an act of ingratitude, as a betrayal of the first order. Maybe waiting for this very moment to strike (or maybe not). Hard to know.

I couldn’t say anything. My advisor kept smiling and didn’t stop even when I picked up my portfolio and hit the door. A smile that I cannot truly render into words, but which I’ve never forgotten. A smile that became, in a way, my entire MFA experience.

I applied for the Stegner, and was promptly rejected.

Do not pass Go.

I had another year of teaching left, if I wanted it, and considering what was waiting for me outside Cornell it was a year I could have used to do more writing, but ultimately I turned it down. No way I could stay. Not under those circumstance. I should have been less proud, should just have eaten the shit and gotten on with it, but for whatever reason I couldn’t. When I saw my advisor in the hallways I didn’t feel like screaming or running; I just felt tired.

That May, I packed my few belongings and took the bus back to NYC. No farewell parties or celebrations. Ended up sharing that bus with one of my peers who in time would become a well-respected academic. Years later he would recount how I cursed my advisor to hell and back. For whatever reason I don’t remember saying anything on that trip. I remember only that the weather was terrible and that my head was pounding.

Could have been worse, I guess. My advisor could have pretended to support my application and written me one of those Bledsoe letters from Ellison’s Invisible Man. Or the experience could have messed with my writing and activism, or embittered me.

But none of that happened. After a year in NYC my anger began to fade, and a year after that no longer vexed me inordinately. I even visited Cornell twice of my own volition and the one time I ran into my advisor I managed to have a civil exchange with them. No kind of reconciliation or apology, but no attacks or denunciation, either — just basic human stuff.

Did they deserve it? Maybe, maybe not, but I know I did.

By then I had begun to realize that my advisor had done me a favor. Given me a chance to express what Samwise would have called my quality. As a poor immigrant kid who’d gone through quite a lot, I knew that in the full scope of my life the Cornell stuff was small kife; and knew also that when the big knife came swinging down — and it would come, the way it comes for all of us — I would be lucky to have had that Cornell experience to fortify me, to whisper Courage in my ear.

In the end I was right on all counts — about the small knife, the big knife, the courage.

2023 was the thirtieth anniversary of the Day Hall Takeover. I didn’t attend the reunion, but from what I gather, courage beat the axe as it always will in the end; the Latino Living Center is still humming along and Helena María Viramontes is still on faculty, kicking Anacaona-level ass and saving students left and right.

As for my advisor, I only think about them at times like these, when our students (and many others of us) are actively protesting the destruction of people, when the knife is bigger than ever and courage and hope and solidarity are about all we have.

Wonderful J! xxx

This is nuts. Felt like I could see advisor's creepy fuckin smile as they turned the attendance book around. What a story.

I hope you share the big knife saga someday.

P.S. did you already have a job lined up in NYC when you left or did you just bounce and say screw it I'll figure it out when I get there?