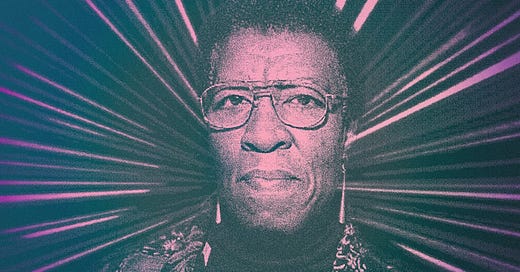

I have friends who survived the campaign cycle by following every nauseating twist —saturation therapy — and other friends who tuned out completely. I tried to preserve my sanity by following at a distance and by reading a lot, especially Octavia Butler (as most of you will have already noticed). Butler is that rarest of artists: a prophet of dark times who is also an immense source of inspiration and wisdom for dark times.

And if we can agree on anything, these are very dark times indeed.

Whether its elections like this one or the challenges facing our struggle for planetary justice, Butler’s fiction offers up a galaxy of radical luminosities that helped keep me oriented and out of the sunken place of despair and complacency —and that were about a thousand times more thoughtful and useful than most of the shit that I got bombarded with.

When it comes to Butler or Morrison or Delany I could go on, but since we’re in the middle of election day I’ll try to keep it short.

Some of her deepest sagacities in no particular order:

In all her fiction, Butler consistently warns against oppressed people taking on the dominator mentality. Egoism, punitivity, lying to oneself, an obsession with political purities — all derangements of the dominator mentality, producing only suffering, and all utterly disastrous for survival.

In opposition to the dominator mentality Butler proposes an ethic of radical survival — predicated on the recognition that in the constricted murderscapes that define life under domination there are no good choices — only choices that are less terrible in the context of our long-term survival. Therefore, we who are dominated must strive always to select the best choice possible out of a whole bunch of bad ones, which Butler seems to argue, is the choice that least harms the population you claim to care about and makes it more likely to survive in the long term.

Butler’s ethic of radical survival has no time for pride or political purity — that’s the prerogative of the dominator, and to mimic it is to harm your chances in ridiculous cosplay — no time for sadopopulism1, either, or those who would throw away their vote in outrage theater. Butler’s ethic of radical survival relies on the strongest weapon of the weak — what I call blasphemous solidarities — a willingness to make common cause with a devil to keep a worse devil at bay, so as to maximize the community’s long-term chances for survival, and eventually achieve true freedom.

As must already be obvious, Butler sees (and in her fiction dramatizes) the danger in short-term thinking — in the impatience of the mayfly revolutionary. The Hollywood / Instagram vision of an impending revolutionary irruption that’s going to rideshare us straight to Wakanda is not only delusion, it is guaranteed to delay whatever Wakanda state is to come. If you think that any of the great evils afflicting us are going to be undone in our lifetimes — either you smoking the muck muck or that’s the wild ego speaking.

Revolutionary struggles are longitudinal, intergenerational luchas2. Focus on getting the community through the now in the best form possible, and the future will take care of the rest. But unless we struggle wisely, fiercely, humbly, blasphemously, longitudinally, there will be no future, in the near or far range.

Plus, thinking that the revolution is imminent is fucking bad for you. Short-term thinking, political impatience, only ever yields disappointment. And disappointment leads inevitably to the abandonment of the mainspring of all revolutionary possibility — hope.

Abandoning hope, given the current state of the world, might seem only logical for many people. Hard to stay in hope, especially after so much disappointment and loss, and more crucially when so much of the politics of hope is mired in some straight up don’t worry be happy normative bullshit.

But Butler’s works knows that we who are not beloved need hope, desperately, radically. Not the vacuous hope of Obama — under which Black life became so dramatically less possible in the words of Saidiya Hartman — but the hope of W.E.B. Du Bois — “a hope that is not hopeful, but not hopeless.”

If Butler’s fiction dramatizes anything it is this: we who are not beloved need hope not as an empty promise, but as a transformative practice of radical potency. Radical hope takes fucking work and sacrifice and countenancing tough choices and lesser devils in order to keep the greater devils at bay. The same not-hopeful-not-hopeless hope that our lost ancestors mobilized to bring us to life is what we in the present all owe to our futures.

Not-hopeful-not-hopeless hope is the work of a lifetime — of many lifetimes — and it’s fucking hard because sometimes there is no hope for us now, only for those to come.

In Butler’s cosmology you vote, not because you’re going to win much or at all —but because the other devil will make shit far worse for the community in the future.

For some who are fed up, with rage helping to salve their disappointment, such blasphemous compromises might be a bridge on their back too far. But what else have we? Our saviors and superheroes and Kwisatz Haderachs are not coming. We are all we have. We have to make the best choice from a shitstorm of bad ones.

We must aspire to be like Lilith, the hero of Butler’s novel Dawn. Lilith, who comes to realize at the novel’s bracing conclusion: If she were lost, others did not have to be. Humanity did not have to be.

Let Lilith’s realization be ours.

The sadopopulist leader, Timothy Snyder argues, is one “whose policies were designed to hurt the most vulnerable part of his own electorate.”

In the majority of Butler’s novels revolutionar, imperfect, hard-earned, often take thousands of years to realize, whether against Doro or the Ooloi.

I’ve been working like crazy to get out the vote for months. I sat down for a moment to take a break and received this text. It got me to stand up and gave me energy to close strong. I’m practicing hope, at least for the next few hours, the next few days, the next few years, the rest of life.

A thousand years? Sounds about right.